EBK Home

Kingdoms

Royalty

Saints

Pedigrees

Archaeology

King Arthur

Adversaries

For Kids

Mail David

Wells

Cathedral

Wells

CathedralExtension and Expansion

John de Villula (alias of Tours) was the first bishop installed in Somerset after the Norman Conquest of 1066. In line with the new regime's policy, he broke up the rural establishment at Wells and, making himself Abbot of the urban community at Bath, changed his title from Bishop of Wells to Bishop of Bath. Half a century later, Bishop Robert, in King Stephen's time, reorganised the canons of Wells and repaired or rebuilt their church. He instituted a dean, precentor, chancellor and treasurer, after the manner of Bishop Osmund of Salisbury, and endowed some twenty prebends. Of his church, hardly anything remains. The present church is largely of late 12th and early 13th century date, the initial work being assigned to Bishop Reginald de Bohun, who died in 1191.

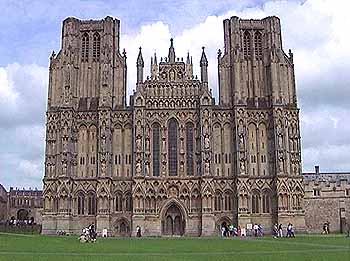

The western bays of the choir, the two transepts and the nave that we see today were completed under successive Bishops and a vast new church in the latest Gothic style - quite an innovation in those days - was largely complete by the time of its dedication in 1239. Bishop Jocelin of Wells had his masons continue with detailed work, however, particularly the decoration of the glorious West front, which continued until about 1260. Bishop Jocelin, a brother of Bishop Hugh II of Lincoln, was one of the bishops who were at the side of Stephen Langton at the signing of Magna Carta. He was exceptionally active in other ways too. His building work, not only included the West front of the Cathedral, but also the bishop's palace, a choristers' school, grammar school, hospital for travellers and a chapel and manor house at Wookey, two miles from Wells. This work stands as that of one of the three "master builders of our holy and beautiful house of St. Andrew in Wells." Associated with Jocelin was Elias of Dereham, a famous designer who died in 1246.

JoceIin's West front, Flaxman styled "a masterpiece of Art indeed . . . England affordeth not the like ". It is flanked on either side by two towers, the upper parts of which are in Perpendicular style, and contains no less than nine tiers of undamaged sculpture. There are about 300 figures, nearly all of heroic proportions, some as much as eight feet in height. In addition, there are smaller statues of angels, saints and prophets, kings and queens of England, bishops and benefactors to the Cathedral, and forty-eight reliefs of Biblical subjects. Notable are the large representations of the Resurrection (containing about 150 figures) and the Last Judgement. "What the ancient glory of that mighty frontal must have been," says Edward Hutton, " when it was covered with silver and gold, with scarlet and purple and blue, and the beauty of all colours, we cannot perhaps realise. It must have been like a page from some glorious Book of Hours. Yet when, on a fortunate evening the sun falls upon it until sunset, it shines, even now, with so great and dazzling a splendour that I have thought to see there that work of praise and worship as it was when new from Bishop Jocelin's hands. There can have been nothing like it in England, nor perhaps in the World. Though it was done with a knowledge of the still earlier work at Amiens and Chartres, in size and in splendour and unity it surpassed them both, and, it is perhaps needless to say, that there is nothing comparable to it left upon earth." Hutton thought the idea of the whole might be more fully understood by turning to the account of the Death, Assumption and Coronation of the Blessed Virgin as given in "The Golden Legend" of Jacobus de Voragine. Here it is told how, at her death, all the Apostles were gathered about her and "at the third hour of the night, came Christ with sweet melody, with the Orders of Angels, the Company of Patriarchs, the Assemblies of Martyrs, the Covenants of Confessors, the Carols of Virgins, in order and with sweet song and melody."

Canon Church gives a different rendering of the great frontal. "Here," he writes, "as men laid their dead to rest, they might look up and see and read this sermon in stones, telling, in one tier of sculptures, the story of man's creation and his fall, his redemption and his resurrection to life. In another tier, they might see the commemoration of the faithful departed, kings and bishops, mailed warriors and ministers of the sanctuary; queens and holy women, types of the honourable of the Earth who had served God standing in their places in life. And then, higher up, these are seen, rising from their graves on the Resurrection morning to stand before the company of Heaven, angels and archangels and the Twelve Apostles of the Lamb and, before the Son of Man seated on his throne, high and lifted up above all, for judgement. Faintly now can we imagine the impressive dignity and glory of this sculptured front as the western sun glowed upon these stately figures, some of matchless grace, as they stood out from under the canopies of their niches, the shadows in the background darkened by artistic colouring. . . . We are here in the presence of one of the monumental records of man's genius and art, mysterious in its origin, telling a story in stone of the Unseen World, such as Dante sang in undying verse later in that century which produced this creation in our midst.''

The important addition of a Chapter House was begun, at Wells, around 1250, but not completed till the time of Dean John Godeley (1305-33). It is reached by a wonderful staircase from the north Choir aisle and is unsurpassed in beauty. The windows, with their delicate tracery, contain fragments of the original glass. Like the Lady Chapel, it is incomparable for its vaulting. "It was," wrote Francis Bond, "in the west of England that the art of Gothic vaulting was first mastered, and it was in the west, first apparently at Wells, that every arch was pointed, and the semi-circular arch exterminated." Later, Godeley man made further enlargements as work began on extending the choir. It was considerably lengthened to join the previously free-standing Lady Chapel to the main church; and the retrochoir and two eastern transepts were erected.

The central cathedral

tower, which rises to a height of 160 feet, was continued in 1318, having,

in earlier years, only been carried up to the level of the roof. It is

thought to have formed a dramatic lantern with triple lights to full

height on each side. It was capped by a small spire. Some years

afterwards, however, it was found that the four massive piers were sinking

and were insufficient to carry the weight of the tower. A catastrophe was

averted with remarkable skill by the medieval builders who placed inverted

arches on three sides under the lantern. Thus supporting the piers from

top to bottom. The whole work, which Glastonbury later copied, was

accomplished with graceful effect. Externally, the central tower was

rebuilt as we see it today after a serious fire in 1439. The south tower

was not begun until after 1386. The north tower, begun in 1424, presents

some slight differences of detail.

The central cathedral

tower, which rises to a height of 160 feet, was continued in 1318, having,

in earlier years, only been carried up to the level of the roof. It is

thought to have formed a dramatic lantern with triple lights to full

height on each side. It was capped by a small spire. Some years

afterwards, however, it was found that the four massive piers were sinking

and were insufficient to carry the weight of the tower. A catastrophe was

averted with remarkable skill by the medieval builders who placed inverted

arches on three sides under the lantern. Thus supporting the piers from

top to bottom. The whole work, which Glastonbury later copied, was

accomplished with graceful effect. Externally, the central tower was

rebuilt as we see it today after a serious fire in 1439. The south tower

was not begun until after 1386. The north tower, begun in 1424, presents

some slight differences of detail.

The Choir contains an elaborate figure of Bishop Ralph of Shrewsbury, who came to Wells in 1329, when the Choir and Lady Chapel were approaching completion. Over the High Altar is the Golden Window, an excellent example of fourteenth-century work. The window, like the Jesse Window now in St. Mary's Church, Shrewsbury, shows the reclining figure of Jesse, from whom springs the Vine, with branches and tendrils enclosing representatives of the line of David. In the centre is the Blessed Virgin and, immediately above, Christ on the Cross. In niches below the window are figures of Our Saviour, St. Peter and St. Andrew, St. Dunstan and St. Patrick (the gifts of an anonymous benefactor) and St. David and St. George given by the Somerset Freemasons in memory of members of that fraternity who fell in the Great War. The three bays of the Choir, east of the magnificent fifteenth century Bishop's throne, form the Presbytery, built in the fourteenth century. While the three western bays belong to the original building and are the oldest part of the existing Cathedral. The Misericord seats, of which there are sixty in the Choir, are finely carved, combining, says Canon Church, " with the early semi-Norman sculpture and the grotesque capitals in the nave and transepts, and with the figures and imagery in stone on the western front, to complete a continuous series of medieval carving remarkable for the blending of grim humour and playfulness, loving study of homely and natural subjects, with grave dignity and mysterious meaning."

The Lady Chapel, a very rich piece of decorated work with a semi-octagonal appearance, forms, with the Transitional bays which connect it with the Choir, what is considered to be the finest eastern end of any Cathedral in this country. Professor EA Freeman wrote of the Chapel, "With the exquisite beauty of the Lady Chapel everyone is familiar; but everyone may not have remarked how distinct it is from the rest of the Church. It would stand perfectly well by itself as a detached building. As it is, it gives an apsidal form to the extreme end of the Church; but it is much more than an apse. It is, in fact, an octagon, no less than the Chapter House, and to its form it owes much of its beauty." To quote Hutton again (who describes the Chapel as " a thing beyond criticism or praise, an immortal and perfect loveliness"): " Here, at Wells, the usual English east end, square and blunt, lacking in fancy and imagination as many have thought, is magically avoided, and all that the subtle French builder achieved with his apsidal chapels is suddenly won by a stroke of genius for this English church, but in a simpler fashion." Francis Bond says the "putting up of an outer ring of four more piers round the western part of the octagon of the Lady Chapel was an intuition of Genius. It makes the vistas into the Retrochoir and Lady Chapel a veritable glimpse into fairy land and provides, here alone in England, a rival to the glorious eastern terminations of Amiens and Le Mans."

Of the excellently proportioned Nave it has been said "there is no nave in which the eye is so irresistibly carried eastward as in that of Wells." Superbly clustered pillars divide it into ten bays, the capitals of each pillar being dexterously and quaintly carved. One capital shows a shoemaker, another a fruit stealer, another, a fox with a goose and another, a man with the toothache. Between the second and third piers, on the north side of the Nave, is the Bubwith Chantry, noteworthy for its cornices and screen work: a beautiful Perpendicular chapel. Opposite is the chantry built for Hugh Sugar, Treasurer of Wells (1460-89). In the north transept, is the famous "Quarter Jack" clock in which the device of a tournament used for recording the hours is not the least of its many quaint features. At the striking of the hours, a company of four mounted men armed with lances conduct a mimic tourney upon a little platform over the dial and a seated figure in knee-breeches kicks a bell at each quarter of an hour. The quarters are sounded outside by two knights in fifteenth-century armour with battle-axes.

The Cloisters, which measure 160 by 150 feet, lie to the south of the Nave. The style of the cloisters, its outer walls and south-east door belongs to the thirteenth century. The present eastern arcade, above which is the Library, was built in Bishop Bubwith's time. The western arcade, with the Audit Room and the Song School over it, was built by Bishop Beckington (1443-65). In the cemetery, east of the Cloisters, stood another Lady Chapel which was rebuilt by Bishop Stillington in about 1490, but was destroyed in 1553. This was the only serious loss which the fabric of the church suffered in those perilous days of the Reformation.

Next in interest is the Bishop's Palace. Its crenellated walls, gateway, and moat were erected in 1343. Inside the grounds are the ruins of the Banqueting Hall, dismantled in 1555 - the largest in England, with the exception of Westminster Hall.

Vicars' Close, with its fifty small houses forming the most perfect Gothic thoroughfare in England, was originally built as the College of Singing Clerks of the Cathedral. Here, time seems to have stood still ever since Bishop Ralph of Shrewsbury designed the Close in the middle of the fourteenth century. The visitor to Wells will also be attracted by the graceful and unique Chain Gate spanning the Bath Road and the ingeniously contrived Water Conduit. For both of these, Wells is indebted to Bishop Beckington. The glorious Parish Church of St. Cuthbert is one of those splendid Perpendicular buildings known in Somerset as "Quarter Cathedrals." It is only from Tor Hill, after having visited St. Andrew's Church itself, that the surpassing loveliness of the noble Cathedral, which has been aptly described as "a precious jewel set in an emerald landscape," can be realised. The rocky crests and tree-clad sides of the Mendips provide an ideal background for the peaceful scene; while, looking westwards, the far-reaching prospect, across moorlands, meadows, coppices and hedgerows, is bounded only by the waters of the Severn Sea.

Edited from "Cathedrals" (1924).

Click for Pre-Conquest Wells Cathedral